on bo burnham, fleabag, and confessional comedy

There is an emerging genre of confessional art born from the minds of people whose coming-of-age were at once marked by perpetual angst as well as being perpetually online and perpetually performing. These are works that explore what it means to live with a brain broken into shards by open tabs, divided attention, and the contested territory of our inner lives. Consider the successes of autofictional endurance trials in literature over the past few years: the popularity of Patricia Lockwood, Hanya Yanagihara, and Ben Lerner, who once remarked that the point of autofiction,

“has never been self-revelation, but an “instrument for examining other things, while also ‘aggressively disavowing; the Great American Novelist position of white universality, which he considers at best ‘pompous’ and pretentious, at worst a “real political danger.”

Yet exploring some of the more intimate territory of our inner lives yields a type of gratification that is not just cathartic, but celebrated by a cultural embrace of a new media tradition of taking labels— woke, based, empathic, neurodivergent, pandemic brain—for the solution itself. This genre of writing too often produces sentiment that is either uniformly critical of the world, or self-acquitting.

As we cautiously envision our lives in the after-times of a pandemic that radically challenged our place amongst others as well as our place vis-à-vis ourselves, there will be attempts to make art of the unprecedented and collective trauma of the pandemic. Some of these will attempt to make sweeping proclamations about what the after-times should look like, how we can heal ourselves from the once-thought paradoxical onslaught of isolation and interpersonal conflict from which we will emerge; others will make laughs from past anxieties, forming disconnected critiques of now laughable inclinations to stockpile toilet paper of those who were fortunate enough to not be one of the nearly four million people who weren’t fortunate enough to hypothesize about retrospectives of the pandemic in the after-times. Certainly, while “nothing is funnier than unhappiness,” unhappiness just by itself is not usually all that funny. What will emerge in the new cultural moment may not be comprehensible to those who are, say, well-adjusted enough to make sense—and not spectacle—of trauma. But to the rest of us they are both a breath of relief and a terror to encounter, a mirror held up to our own frazzled, fractured consciousness.

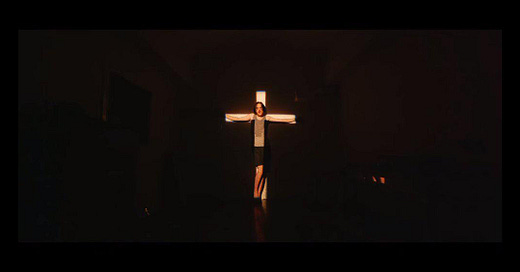

Indeed, bawdiness and wit can be cranked so high that they can easily distract a viewer from the disturbing undercurrents of shame and guilt that give narrative its energy and stakes. With an eye towards the pre-pandemic past, I’m thinking of Fleabag, the fourth-wall breaking series from Phoebe Waller-Bridge which concluded in 2019 after a two series run; and with a cautious peek at a potential future, Inside, the new Netflix special by Bo Burnham, one of the auteurs of the perpetually-online mind. Burnham captures, with dexterous clairvoyance, the unmoored and listless feeling of being incredibly present in isolation during the pandemic. The ninety-minute assemblage, which Burnham wrote and directed in quarantine, is in no way a traditional comedy special, in which a person tells jokes while standing in front of an audience. It mixes laughter with pain, introspection and outrospection. And it features a performer trying to make sense of it all, both the immediate and the larger context of life at this moment, and nearly driving himself batshit in the process. What have we gotten ourselves into? Where do we go from here? And is a year indoors the karmic price we had to pay for this mess we've made of everything? It contains barely any spoken punch lines at all outside of a few canned, tinny segments, in which the bits feel deliberately hackneyed and insistently out-of-date. (Why don’t pirates laminate their treasure maps?)

Waller-Bridge and Burnham offer two snapshots of comedy on either side of the pandemic. One of my last by-association brushes with the experience of live performance prior to the pandemic was hearing a friend recount the joy of a National Theater Live performance of Fleabag. One day we’re all sitting in a theater watching a recording of a stage-adaptation of a television series and the next, we find ourselves in front of our TVs gawking at a made-for-living-room reinvention of a historically live in-person performance. Chaos. Both are very funny stories about unhappiness as well as unhappy stories about what resists being staged for laughs. Obviously tormented over the two years spanning the series, Fleabag never recounts the events, never claims responsibility, never speaks of guilt or remorse. But the difference that a pandemic has made is that where it was once clear what the audience wanted for Fleabag (to fuck and to do what one does in the same confessional box, and what she has refused to do for the show’s entire run, unburden herself and confess her actual sin), it is less clear what to desire of pandemic comedy. Almost none of Inside is stand-up, although Burnham occasionally begins to do traditional comedy and finds that it turns sour or uninspired, and that it makes no sense personally nor performatively. How to receive this special is complicated by the fact that we see Burnham himself struggling to make sense of what it is that he’s making: the playing out in itself of the tension between staying in bed, staying in the dark, staying alone and creating, busying, and telling jokes. How many jokes do you make about having had no human contact and losing access to and closing yourself off from relationships, and how much do you candidly acknowledge that you have no idea how long you can go on like this?

In the confessional box near the series’ end of Fleabag, Hot Priest, as priests do, asks Fleabag to tell him her sins. Confess! Unburden yourself! But Fleabag does not. The show’s arc appears to depict utter failure; Fleabag refuses to confess her guilt and asks to be relieved of the responsibility for her own actions in perpetuity. The priest pounces. But then, it doesn’t feel like much of a failure, does it?

Nobel laureate novelist John Maxwell Coetzee reflecting on a literary tradition of confession— Rousseau, Dostoevsky and Tolstoy—writes that at the heart of confession is desire itself. One always confesses to someone and there is always a motive, one which no one can guarantee is a pure one: the fear of punishment, the desire for absolution, the pleasures of self-abasement or even pride, but above all, always, shame. Confession is, as Dostoevsky’s Idiot says, after all, only “a special form of bragging.” Where for Dostoevsky bragging lived a life between foes and between friends—in conversation, in interpersonal space—the type of gains that are courted in confession for us more recently can be found in the medium of presentation itself, embedded in the form that envelops even the communicated content. Fleabag makes clear enough the ways in which confession is always implicated in self-presentation and self-performance. Perhaps then, it is not simply a failure on Fleabag’s part that as far as her one true sin is concerned, she doesn’t confess. For all her admission and performance of failure to our delight, for all the remarkable honesty and nakedness of the show, and precisely because of them, it is fitting that at its heart is a refusal to hand her guilt over. Perhaps this refusal to confess marks not a failure to assume responsibility but the only genuine form of doing so.

Actual moral failing, our propensity to injure and inflict irrevocable pain and loss, however incidental, is not an indiscretion to be transformed into a punch line and leveraged for self-imaging. Fleabag does not fail her late friend Boo by refusing to confess her wrongdoing, for to confess it now would inevitably make it part of her affair with Hot Priest, that is to say, a part of her show. Self-improvement as an aspiration, or a subject matter, is fine, and part of that project necessarily involves ‘naming and taming’ our individual struggles. It’s easy to say this cultural embrace of normalizing talking about our neuroses only represents a productive destigmatization of mental health, or to take the opposite stand and proclaim us over-pathologized, or even to be Derridean and say that both can be simultaneously true all at once. But I think here we might be able to find simpler resolution, which is that the effect of confession—whether it becomes unintentionally self-serving or not—depends on who it is that the act of confession is directed towards. As a work of art, Fleabag thus displays to us guilt in its elusive fullness, and ineliminable privacy. For all the tribunals and public disapproval, absolution can never come fully from someone else, if at all. Confession is a private act, and not meant for a public jury, because to fathom the effect of a jury assumes the possibility that there remains something to be socially or culturally gained (acquittal, ideally). Taking up this implication more broadly, discourses offer a means of participation, whether that participation is conscious or not, that regulates membership in (and out) of discursive fields. It is in this sense that Rey Chow (writing about postcolonial confessions) and Michel Foucault (writing about secular queer confession) invoke the phrase “the speaker’s benefit” to describe those who speak of and against struggle and repression as though they have, by performing such a transgressive speech act, freed themselves.

What this leaves us with is a form of expression that is inadequate for connecting with and describing the reality of the world. This is why, toward the end of the second season, Fleabag begins to turn away the camera. First, she does it when she’s having sex with the priest. Then at series end, Fleabag again asks the camera to stay behind while she walks away. She has exposed herself enough, she has paid what she could, she no longer needs to perform her shame for our pleasure. She is, perhaps, free— free to live a life of which neither a camera, nor we, are a part. But this itself is a luxury that we may no longer be afforded after our collective failings and individual struggles during and after the pandemic.

Performance that stubbornly walks a line between irony and sincerity, between intimacy and distance, honesty and self-acquittal is a complicated form. Sometimes, the ambiguous tease of “Am I kidding or not?” is expected to be so satisfying and complicating that the content itself forgets to make a point. That’s not the case with Burnham. Where it would have been easy to disappear in the comedic innards of his performance, Burnham never attempts to obfuscate or turn away from the unfortunate conditions of possibility that backgrounds the entire special. Even as we see his nervous mind emerge from the throws of the busy project and the confines of his studio apartment, it is into the same light that will serve as judge, jury, and executioner.

If for Fleabag, the comedy ends at the same time as the confession, Burnham stages the work of a new type of comedy that remains incomplete, one that fundamentally challenges the role of the comedian and performer and takes in self-reflexively the weight of confession and comedy as a perpetually unresolved and ongoing project that cannot be indifferent to that which have haunted us for the better part of two years. Comedy is not possible, except on the foundation of the pandemic itself. The intention is that comedy, and all art, cannot simply resurrect or reconstruct pandemic experiences as if it was a blip—that we no longer have the privilege of turning away from the camera the moment that the confession ends—that confession must live on beyond the discursive act. Perhaps it signals a rupture in comedy for those who recognize that in the path of terror of a virus that was indiscriminate in its ability to kill and spread loss, it was ultimately arbitrary who was spared and who gets to enjoy laughter on the other side. Perhaps Burnham’s lead is a precedent for pandemic art in the after-times. There's something profound and unnerving about Inside that speaks to the careening and difficult thoughts that I think haunted a particular kind of person. Burnham highlights what he's always been so adept at, which is showing the artifice of everything he does, the conditions of performance and comedic possibility. From the first segment, when he questions the aptness of his own performance— taking place after a period of his own struggle with anxiety that led to a multiyear hiatus from standup and being made possible by an anxiety which we all find ourselves sharing— he initiates a continual staging and re-staging of the work of comedy as unsettling the position of comedy in the foreground when it is the what’s happening outside of his cloistered studio that really backlight the production. The reality of the pandemic is the backdrop and the show. There is no ending, only a series of new challenging beginnings. What a show it is.